In ancient Greece, the stadium (stadion) was more than a place to watch sports—it was a sacred space that celebrated physical excellence, civic pride, and the divine. These long, open-air venues were the heart of athletic competition, especially during religious festivals dedicated to gods like Zeus and Apollo. From the famous stadium at Olympia to lesser-known regional venues, stadiums were where athletes became heroes, and where communities came together in admiration and awe.

What Was a Greek Stadium?

The word “stadion” originally referred to a unit of length—approximately 600 Greek feet (about 180–200 meters). Eventually, the term came to describe the track and the venue where footraces and other athletic events took place.

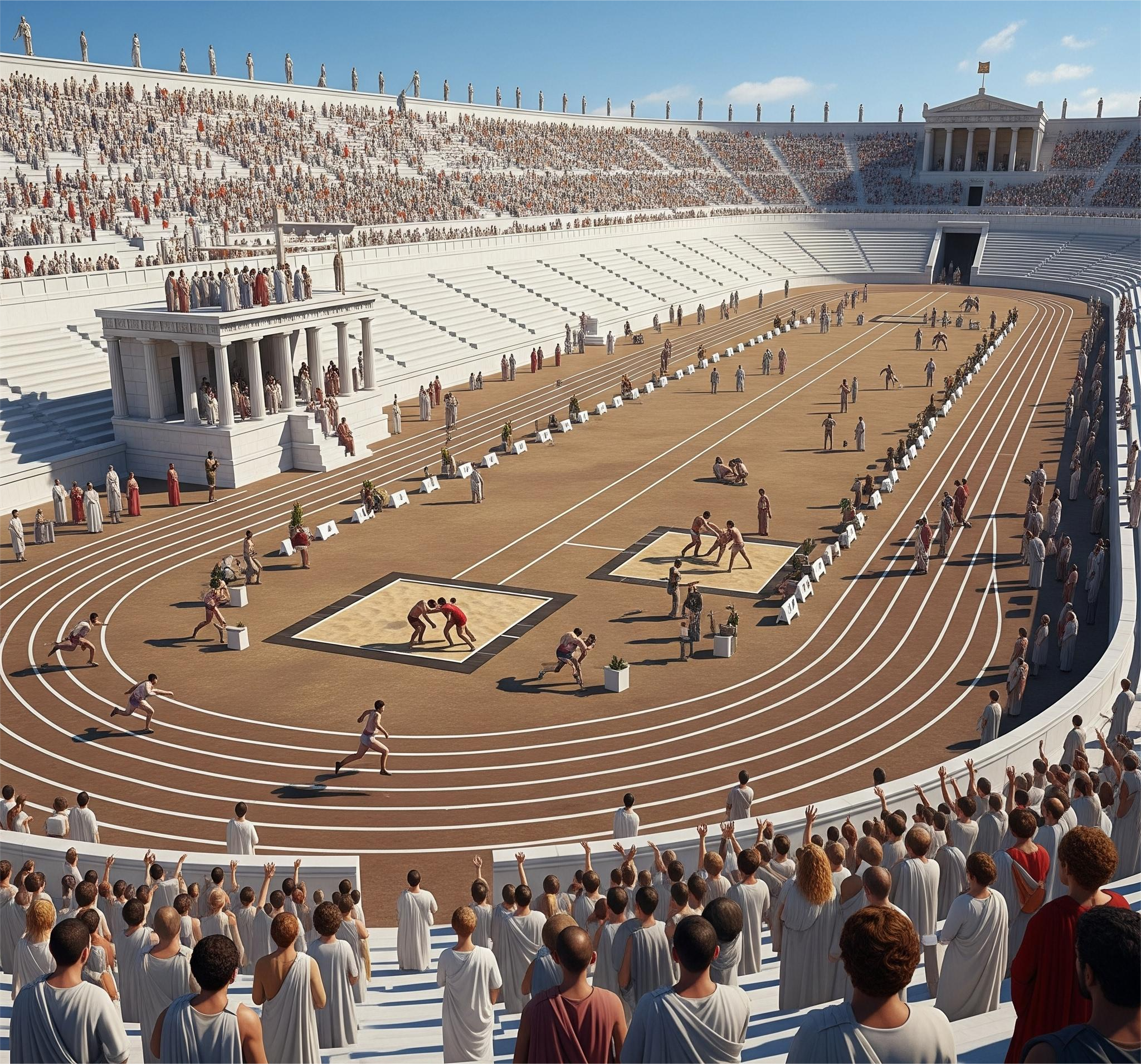

Greek stadiums were U-shaped or elongated ovals, built into natural slopes when possible for tiered seating. Unlike modern stadiums, there were no permanent grandstands—spectators often sat or stood on grassy embankments or stone tiers.

Stadium Layout: Simplicity with Purpose

Most ancient stadiums followed a simple but effective layout:

Track (Dromos): A straight, flat racing surface made of packed earth or sand, typically about 192 meters long.

Starting Line (Balbis): A stone or wooden strip marking the start, often with slots to anchor runners' feet.

Turning Posts (Terminus): At either end, especially for races requiring multiple laps.

Spectator Embankments: Hillsides or built terraces for crowds; the wealthiest or most honored guests sat closest to the action.

Entrance Tunnel (Krypte Esodos): A vaulted passage used by athletes and VIPs, especially at Olympia.

Altar or Dedications: Some stadiums had shrines or dedications to gods, blending sport with sacred ritual.

Athletic Events and Their Meaning

Stadiums hosted footraces, which were the original Olympic events:

Stadion race – a sprint of one length (~200m)

Diaulos – a double stadion (~400m)

Dolichos – a long-distance race (up to 24 stadia)

Hoplite race (hoplitodromos) – run in armor with a shield, simulating battle readiness

These races weren’t just about speed—they celebrated arete (excellence), discipline, and honor before the gods. Victors won olive wreaths, fame, and often lifelong privileges, including free meals, statues, and songs in their honor.

Sacred and Civic Role

Greek stadiums were integral to religious festivals:

At Olympia, races were part of the Olympic Games in honor of Zeus.

At Delphi, the Pythian Games celebrated Apollo.

In Nemea and Isthmia, similar festivals honored Zeus and Poseidon, respectively.

But stadiums also served public and political purposes:

Mass gatherings: Citizens could assemble to hear announcements or honor war heroes.

Diplomatic meetings: Festivals often attracted ambassadors and dignitaries.

Unity and rivalry: While fostering Panhellenic unity, games also stoked inter-city competition.

Famous Greek Stadiums

Olympia Stadium

Among the oldest (constructed ca. 5th century BCE).

Could hold up to 40,000 spectators.

Set in a sacred grove (Altis) near the temple of Zeus.

Delphi Stadium

Built high above the sanctuary of Apollo.

Stone seating added in the 2nd century CE.

Hosted athletic and musical contests during the Pythian Games.

Epidaurus Stadium

Located near the famous healing sanctuary of Asclepius.

Blended sport and health—perfect for the ancient view of a balanced life.

Beyond Competition: Cultural Significance

Stadiums weren’t just about muscle and medals. They reflected Greek values:

Education and virtue: Athletics were part of paideia—the education of citizens.

Equality and fairness: Events were judged strictly, with punishments for cheating.

Ritual purity: Athletes had to bathe, oil themselves, and offer prayers before competing.

Legacy and Influence

The design of Greek stadiums directly influenced Roman arenas and eventually modern sports architecture. The very word “stadium” endures today, from the Olympic arenas to local high school tracks.

Even in ruin, these ancient venues evoke the spirit of unity, competition, and devotion that defined the Greek world.